So you want to use a price oracle

Nov 09, 2020 | samczsun

In late 2019, I published a post titled “Taking undercollateralized loans for fun and for profit”. In it, I described an economic attack on Ethereum dApps that rely on accurate price data for one or more tokens. It's currently late 2020 and unfortunately numerous projects have since made very similar mistakes, with the most recent example being the Harvest Finance hack which resulted in a collective loss of 33MM USD for protocol users.

While developers are familiar with vulnerabilities like reentrancy, price oracle manipulation is clearly not something that is often considered. Conversely, exploits based on reentrancy have fallen over the years while exploits based on price oracle manipulation are now on the rise. As such, I decided it was time that someone published a definitive resource on price oracle manipulation.

This post is broken down into three sections. For those who are unfamiliar with the subject, there is an introduction to oracles and oracle manipulation. Those who want to test their knowledge may skip ahead to the case studies, where we review past oracle-related vulnerabilities and exploits. Finally, we wrap up with some techniques developers can apply to protect their projects from price oracle manipulation.

Oracle manipulation in real life

Wednesday, December 1st, 2015. Your name is David Spargo and you’re at the Peking Duk concert in Melbourne, Australia. You’d like to meet the band in person but between you and backstage access stand two security guards, and there’s no way they would let some average Joe walk right in.

How would the security guards react, you wonder, if you simply acted like you belonged. Family members would surely be allowed to visit the band backstage, so all you had to do was convince the security guards that you were a relative. You think about it for a bit and come up with a plan that can only be described as genius or absolutely bonkers.

After quickly setting everything up, you confidently walk up to the security guards. You introduce yourself as David Spargo, family of Peking Duk. When the guard asks for proof, you show them the irrefutable evidence - Wikipedia.

o

The guard waves you through and asks you to wait. A minute passes, then two. After five minutes, you wonder if you should make a run for it before law enforcement makes an appearance. As you’re about to bail, Reuben Styles walks up and introduces himself. You walk with him to the green room where the band was so impressed with your ingenuity that you end up sharing a few beers together. Later, they share what happened on their Facebook page.

What is a price oracle?

A price oracle, generously speaking, is anything that you consult for price information. When Pam asks Dwight for the cash value of a Schrute Buck, Dwight is acting as a price oracle.

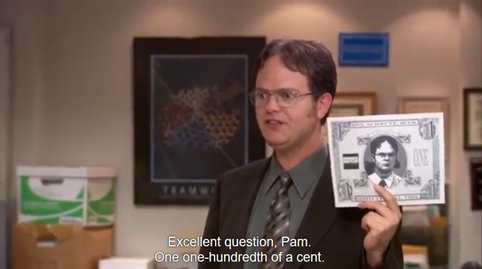

On Ethereum, where everything is a smart contract, so too are price oracles. As such, it’s more useful to distinguish between how the price oracle gets its price information. In one approach, you can simply take the existing off-chain price data from price APIs or exchanges and bring it on-chain. In the other, you can calculate the instantaneous price by consulting on-chain decentralized exchanges.

Both options have their respective advantages and disadvantages. Off-chain data is generally slower to react to volatility, which may be good or bad depending on what you’re trying to use it for. It typically requires a handful of privileged users to push the data on-chain though, so you have to trust that they won’t turn evil and can’t be coerced into pushing bad updates. On-chain data doesn’t require any privileged access and is always up-to-date, but this means that it’s easily manipulated by attackers which can lead to catastrophic failures.

What could possibly go wrong?

Let’s take a look at a few cases where a poorly integrated price oracle resulted in significant financial damage to a DeFi project.

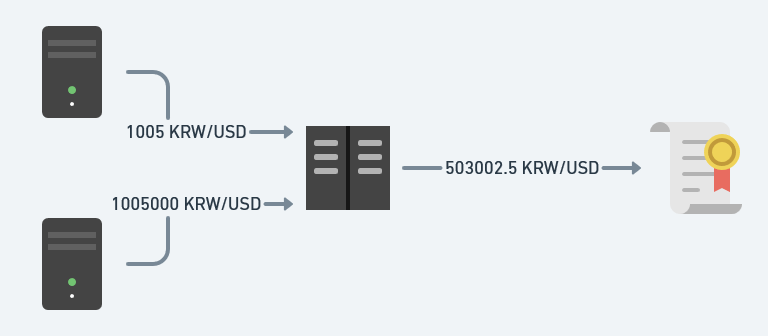

Synthetix sKRW Oracle Malfunction

Synthetix is a derivatives platform which allows users to be exposed to assets such as other currencies. To facilitate this, Synthetix (at the time) relied on a custom off-chain price feed implementation wherein an aggregate price calculated from a secret set of price feeds was posted on-chain at a fixed interval. These prices then allowed users to take long or short positions against supported assets.

On June 25, 2019, one of the price feeds that Synthetix relied on mis-reported the price of the Korean Won to be 1000x higher than the true rate. Due to additional errors elsewhere in the price oracle system, this price was accepted by the system and posted on-chain, where a trading bot quickly traded in and out of the sKRW market.

In total, the bot was able to earn a profit of over 1B USD, although the Synthetix team was able to negotiate with the trader to return the funds in exchange for a bug bounty.

Synthetix correctly implemented the oracle contract and pulled prices from multiple sources in order to prevent traders from predicting price changes before they were published on-chain. However, an isolated case of one upstream price feed malfunctioning resulted in a devastating attack. This illustrates the risk of using a price oracle which uses off-chain data: you don't know how the price is calculated, so your system must be carefully designed such that all potential failure modes are handled properly.

Undercollateralized Loans

As mentioned earlier, I published a post in September 2019 outlining the risks associated with using price oracles that relied on on-chain data. While I highly recommend reading the original post, it is quite long and heavy in technical details which may make it hard to digest. Therefore, I’ll be providing a simplified explanation here.

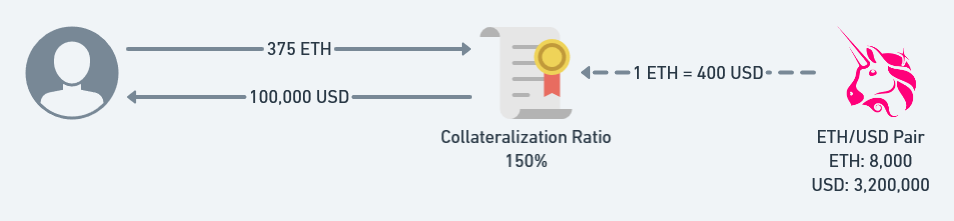

Imagine you wanted to bring decentralized lending to the blockchain. Users are allowed to deposit assets as collateral and borrow other assets up to a certain amount determined by the value of the assets they’ve deposited. Let’s assume that a user wants to borrow USD using ETH as collateral, that the current price of ETH is 400 USD, and that the collateralization ratio is 150%.

If the user deposits 375 ETH, they’ll have deposited 150,000 USD of collateral. They can borrow 1 USD for every 1.5 USD of collateral, so they’ll be able to borrow a maximum 100,000 USD from the system.

But of course, on the blockchain it’s not as simple as simply declaring that 1 ETH is worth 400 USD because a malicious user could simply declare that 1 ETH is worth 1,000 USD and then take all the money from the system. As such, it’s tempting for developers to reach for the nearest price oracle shaped interface, such as the current spot price on Uniswap, Kyber, or another decentralized exchange.

At first glance, this appears to be the correct thing to do. After all, Uniswap prices are always roughly correct whenever you want to buy or sell ETH as any deviations are quickly correct by arbitrageurs. However, as it turns out, the spot price on a decentralized exchange may be wildly incorrect during a transaction as shown in the example below.

Consider how a Uniswap reserve functions. The price is calculated based on the amount of assets held by the reserve, but the assets held by the reserve changes as users trade between ETH and USD. What if a malicious user performs a trade before and after taking a loan from your platform?

Before the user takes out a loan, they buy 5,000 ETH for 2,000,000 USD. The Uniswap exchange now calculates the price to be 1 ETH = 1,733.33 USD. Now, their 375 ETH can act as collateral for up to 433,333.33 USD worth of assets, which they borrow. Finally, they trade back the 5,000 ETH for their original 2,000,000 USD, which resets the price. The net result is that your loan platform just allowed the user to borrow an additional 333,333.33 USD without putting up any collateral.

This case study illustrates the most common mistake when using a decentralized exchange as a price oracle - an attacker has almost full control over the price during a transaction and trying to read that price accurately is like reading the weight on a scale before it’s finished settling. You’ll probably get the wrong number and depending on the situation it might cost you a lot of money.

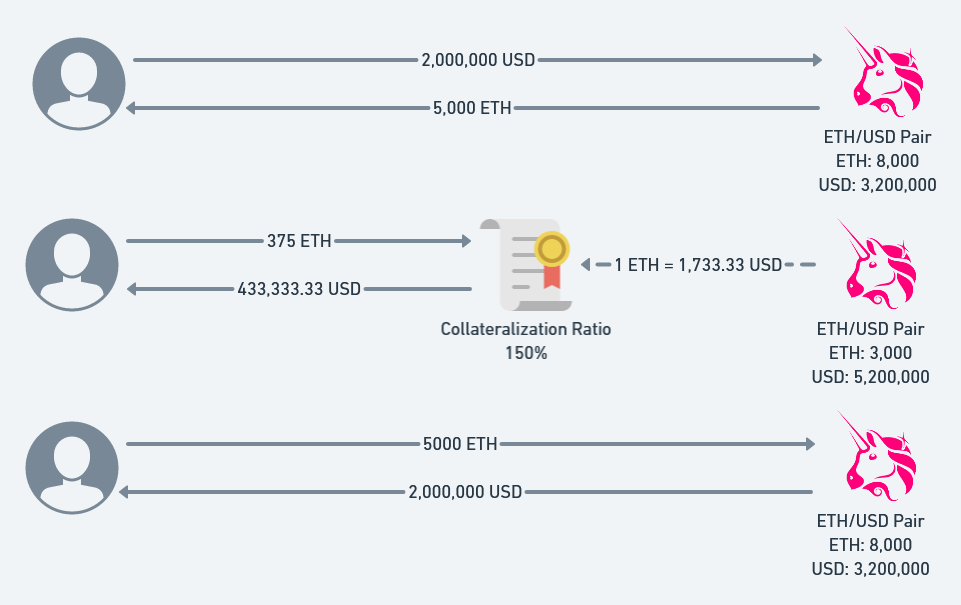

Synthetix MKR Manipulation

In December 2019, Synthetix suffered another attack as a result of price oracle manipulation. What’s notable about this one is that it crossed the barrier between on-chain price data and off-chain price data.

Reddit user u/MusaTheRedGuard observed that an attacker was making some very suspicious trades against sMKR and iMKR (inverse MKR). The attacker first purchased a long position on MKR by buying sMKR, then purchased large quantities of MKR from the Uniswap ETH/MKR pair. After waiting a while, the attacker sold their sMKR for iMKR and sold their MKR back to Uniswap. They then repeated this process.

Behind the scenes, the attacker’s trades through Uniswap allowed them to move the price of MKR on Synthetix at will. This was likely because the off-chain price feed that Synthetix relied on was in fact relying on the on-chain price of MKR, and there wasn’t enough liquidity for arbitrageurs to reset the market back to optimal conditions.

This incident illustrates the fact that even if you think you’re using off-chain price data, you may still actually be using on-chain price data and you may still be exposed to the intricacies involved with using that data.

The bZx Hack

In February 2020, bZx was hacked twice over the span of several days for approximately 1MM USD. You can find an excellent technical analysis of both hacks written by palkeo here, but we will only be looking at the second hack.

In the second hack, the attacker first purchased nearly all of the sUSD on Kyber using ETH. Then, the attacker purchased a second batch of sUSD from Synthetix itself and deposited it on bZx. Using the sUSD as collateral, the attacker borrowed the maximum amount of ETH they were allowed to. They then sold back the sUSD to Kyber.

If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll recognize this as essentially the same undercollateralized loan attack, but using a different collateral and a different decentralized exchange.

yVault Bug

On July 25, 2020, I reported a bug to yEarn regarding the launch of their new yVault contracts. You can read the official writeup about this bug here, but I will briefly summarize it below.

The yVault system allows users to deposit a token and earn yield on it without needing to manage it themselves. Internally, the vault tracks the total amount of yVault tokens minted as well as the total amount of underlying tokens deposited. The worth of a single yVault token is given by the ratio of tokens minted to tokens deposited. Any yield the vault earns is spread across all minted yVault tokens (and therefore, across all yVault token holders).

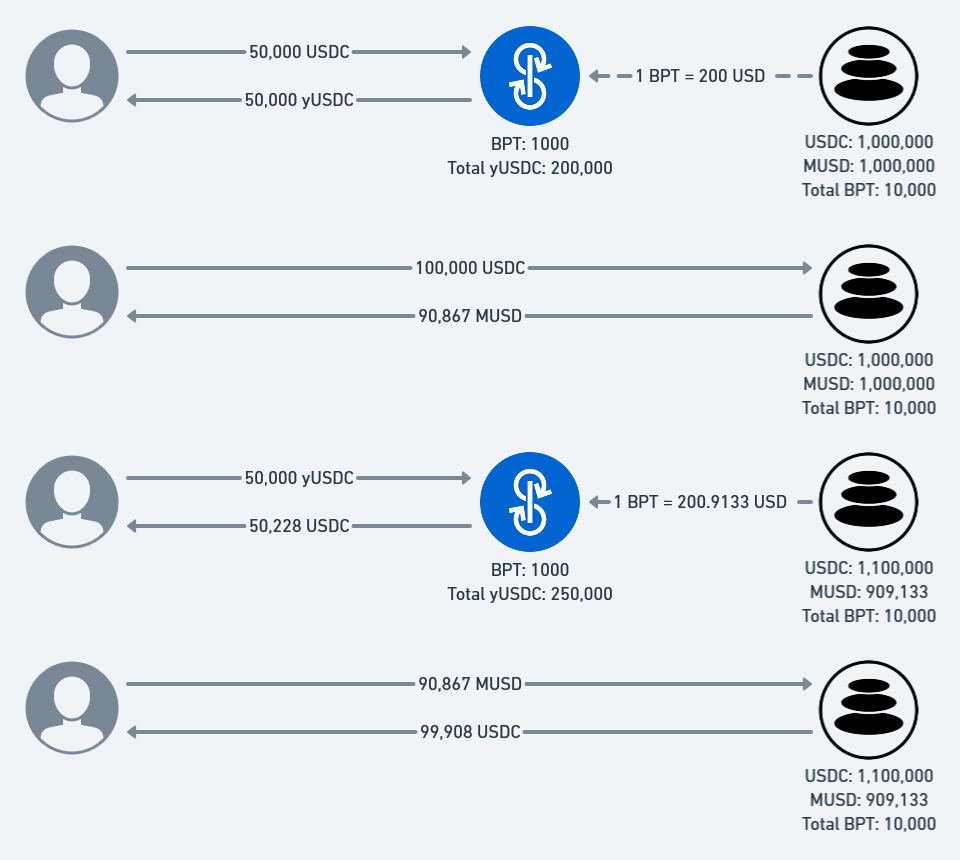

The first yVault allowed users to earn yield on USDC by supplying liquidity to the Balancer MUSD/USDC pool. When a user supplies liquidity to Balancer pools, they receive BPT in return which can be redeemed for a proportion of the pool. As such, the yVault calculated the value of its holdings based on the amount of MUSD/USDC which could be redeemed with its BPT.

This seems like the correct implementation, but unfortunately the same principle as given before applies - the state of the Balancer pool during a transaction is not stable and cannot be trusted. In this case, because of the bonding curve that Balancer chose, a user who swaps between from USDC to MUSD will not receive a 1:1 exchange rate, but will in fact leave behind some MUSD in the pool. This means that the value of BPT can be temporarily inflated, which allows an attacker to manipulate the price at will and subsequently drain the vault.

This incident shows that price oracles are not always conveniently labelled as such, and that developers need to be vigilant about what sort of data they’re ingesting and consider whether that data can be easily manipulated by an unprivileged user.

Harvest Finance Hack

On October 26, 2020, an unknown user hacked the Harvest Finance pools using a technique that you can probably guess by now. You can read the official post-mortem here, but once again I’ll summarize it for you: the attacker deflated the price of USDC in the Curve pool by performing a trade, entered the Harvest pool at the reduced price, restored the price by reversing the earlier trade, and exited the Harvest pool at a higher price. This resulted in over 33MM USD of losses.

How do I protect myself?

By now, I hope that you’ve learned to recognize the common thread - it's not always obvious that you're using a price oracle and if you don't follow the proper precautions, an attacker could trick your protocol into sending them all of your money. While there’s no one-size-fits-all fix that can be prescribed, here are a few solutions that have worked for other projects in the past. Maybe one of them will apply to you too.

Shallow Markets, No Diving

Like diving into the shallow end of a pool, diving into a shallow market is painful and might result in significant expenses which will change your life forever. Before you even consider the intricacies of the specific price oracle you’re planning to use, consider whether the token is liquid enough to warrant integration with your platform.

A Bird in the Hand is Worth Two in the Bush

It may be mesmerizing to see the potential exchange rate on Uniswap, but nothing’s final until you actually click trade and the tokens are sitting in your wallet. Similarly, the best way to know for sure the exchange rate between two assets is to simply swap the assets directly. This approach is great because there’s no take-backs and no what-ifs. However, it may not work for protocols such as lending platforms which are required to hold on to the original asset.

Almost Decentralized Oracles

One way to summarize the problem with oracles that rely on on-chain data is that they’re a little too up-to-date. If that’s the case, why not introduce a bit of artificial delay? Write a contract which updates itself with the latest price from a decentralized exchange like Uniswap, but only when requested by a small group of privileged users. Now even if an attacker can manipulate the price, they can’t get your protocol to actually use it.

This approach is really simple to implement and is a quick win, but there are a few drawbacks - in times of chain congestion you might not be able to update the price as quickly as you’d like, and you’re still vulnerable to sandwich attacks. Also, now your users need to trust that you’ll actually keep the price updated.

Speed Bumps

Manipulating price oracles is a time-sensitive operation because arbitrageurs are always watching and would love the opportunity to optimize any suboptimal markets. If an attacker wants to minimize risk, they’ll want to do the two trades required to manipulate a price oracle in a single transaction so there’s no chance that an arbitrageur can jump in the middle. As a protocol developer, if your system supports it, it may be enough to simply implement a delay of as short as 1 block between a user entering and exiting your system.

Of course, this might impact composability and miner collaboration with traders is on the rise. In the future, it may be possible for bad actors to perform price oracle manipulation across multiple transactions knowing that the miner they’ve partnered with will guarantee that no one can jump in the middle and take a bite out of their earnings.

Time-Weighted Average Price (TWAP)

Uniswap V2 introduced a TWAP oracle for on-chain developers to use. The documentation goes into more detail on the exact security guarantees that the oracle provides, but in general for large pools over a long period of time with no chain congestion, the TWAP oracle is highly resistant to oracle manipulation attacks. However, due to the nature of its implementation, it may not respond quickly enough to moments of high market volatility and only works for assets for which there is already a liquid token on-chain.

M-of-N Reporters

Sometimes they say that if you want something done right, you do it yourself. What if you gather up N trusted friends and ask them to submit what they think is the right price on-chain, and the best M answers becomes the current price?

This approach is used by many large projects today: Maker runs a set of price feeds operated by trusted entities, Compound created the Open Oracle and features reporters such as Coinbase, and Chainlink aggregates price data from Chainlink operators and exposes it on-chain. Just keep in mind that if you choose to use one of these solutions, you’ve now delegated trust to a third party and your users will have to do the same. Requiring reporters to manually post updates on-chain also means that during times of high market volatility and chain congestion, price updates may not arrive on time.

Conclusion

Price oracles are a critical, but often overlooked, component of DeFi security. Safely using price oracles is hard and there’s plenty of ways to shoot both yourself and your users in the foot. In this post, we covered past examples of price oracle manipulation and established that reading price information during the middle of a transaction may be unsafe and could result in catastrophic financial damage. We also discussed a few techniques other projects have used to combat price oracle manipulation in the past. In the end though, every situation is unique and you might find yourself unsure whether you’re using a price oracle correctly. If this is the case, feel free to reach out for advice!

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Dan Robinson and Georgios Konstantopoulos for reviewing this post, and to @zdhu_ and mongolsteppe for pointing out an error.

Disclaimer: This post is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any investment and should not be used in the evaluation of the merits of making any investment decision. It should not be relied upon for accounting, legal or tax advice or investment recommendations. This post reflects the current opinions of the authors and is not made on behalf of Paradigm or its affiliates and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Paradigm, its affiliates or individuals associated with Paradigm. The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without being updated.